As I write, my heart aches. Literally. I have a sensation in my heart centre area that feels both like the skin has been ripped off and like I've been punched or a large object has landed on me there.

I mention this as I finally take some time to reflect on attending the most recent Tse Tsa Watle Speakers Series meeting at Royal Roads University (where I teach in both the School of Communication and Culture and the International Study Group) because my own sensitivities are directly related to the dilemmas of Tse Tsa Watle.

What is Tse Tsa Watle?

In the Cowichan language, RRU publicity materials say, it means "coming together to help one another." As a person who has attended a couple of Tse Tsa Watle meetings, I see it as a place for holding a space for aboriginal ways of being (i.e., "coming together to help one another") within the institution. The meetings take place once a month for 2 hours.

Dilemma: how does the aboriginal way exist in a monthly 2-hour meeting that is optional for people to attend? How does "coming together to help one another" look in an institution that only works in blocks of time dedicated to specific purposes, which are created in a complex and not very transparent political environment and are completely dependent on budgetary constraints?

A grave, humble woman, Dr. Pakki Chipps, spoke to us about plant medicine. She spoke about ethnobotany as well as her knowledge from her First Nations family. She told us that much of what she knows cannot be shared because the understandings of working with plant medicine are passed down through families and the knowledge is considered private and sacred; sacredness, privacy and efficacy are related. She also told us that her family (and other First Nations people) worked for centuries in a practice where living with, knowing about, and using plants is gentle and completely connected.

Dilemma: in our culture (enshrined by universities) where everything (literally every thing) is separated into ownership structures and legal entities and categories (and roles and disciplines and departments) so we can pronounce it known and knowable and then act, how can we learn from a culture of "being with," in which sacred and science are the same thing?

In RRU publicity material, Pakki Chipps is described as a woman with a BA, MA, PhD and "a status member of the Beecher Bay First Nation on southern-western Vancouver Island, with Danish and Illulisaht (Greenland Inuit) ancestry. Her doctoral degree in Education/Curriculum and Instruction concentrated on curriculum development, educational technology, multimedia development and environmental studies, specializing in ethnobotany. She taught environmental studies at UVic and returned, two years ago, from teaching in Greenland for two years." This accomplished woman, when I asked if there was a way for my children to learn about being with native plants, answered that she likes to speak at schools and only asks for gas money.

Dr. Chipps spoke about how residential schooling caused a near complete breakdown in passing on of traditional plant knowledge, not only through the disconnection of elders and younger people; but also simply through lost knowledge of locations; and through loss of plant habitat caused by development, introduced plant species, and such. A woman at the meeting who seemed to have a role within the university kindly offered that perhaps there might be a way for Dr. Chipps to contribute to creating a native plant garden at the new First Nations building on campus. That woman suggested that such a tangible project could be a prospect to receive funding.

Dilemma: how can we benefit from the wisdom of people like Pakki Chipps when we are forced to only consider "tangible" advantages?

Dilemma: what "purpose" would a native plant garden on campus serve? (I suggest that it could only exist as a simulacrum, a fake exhibit that could never be used as a source of plant medicine.)

My heartaches, as I'm writing this, are intense. My experience of listening to Pakki Chipps was a dialed up version of my everyday paradox-holding existence. Both times that I have attended Tse Tsa Watle, I have felt, beyond these dilemmas which I have illustrated above, an even bigger elephant in the room: pain.

While Dr. Chipps told us stories and shared information about plants, every remark she made touched on the destruction of aboriginal people, ways, habitat, and wisdom. Not because she made a point of doing so but because she simply spoke knowledgeably, honestly, and matter-of-factly about plant medicine. There is no way to discuss plant medicine and leave out the rest of the devastating historical picture.

But, in a culture where compartmentalization is not only the norm but the ideal, it is a simple matter to leave out pesky emotion-charged information. I'm not saying that discussions of colonialism or feminism or cultural criticism, etc., don't take place. I am saying that slotting discussions into those categories might be a simple and effective way to neutralize and minimize the pain of such discussions. I'm also saying that our culture's slotting of these difficult discussions somehow renders them nonexistent in huge areas of discourse.

Dilemma: when what we know and discuss and learn is disconnected from feeling and when painful and harmful practices are discussed without being felt, how does this affect our humanity?

For myself, I struggle being on the earth. I have done since I have been a conscious person. I have worked on serious physical health problems and emotional pain for decades. The pain I feel is directly related to the sadness of aboriginal history. I have come to understand that my being cannot reconcile living in this world of denial of harm and perpetuation of domination.

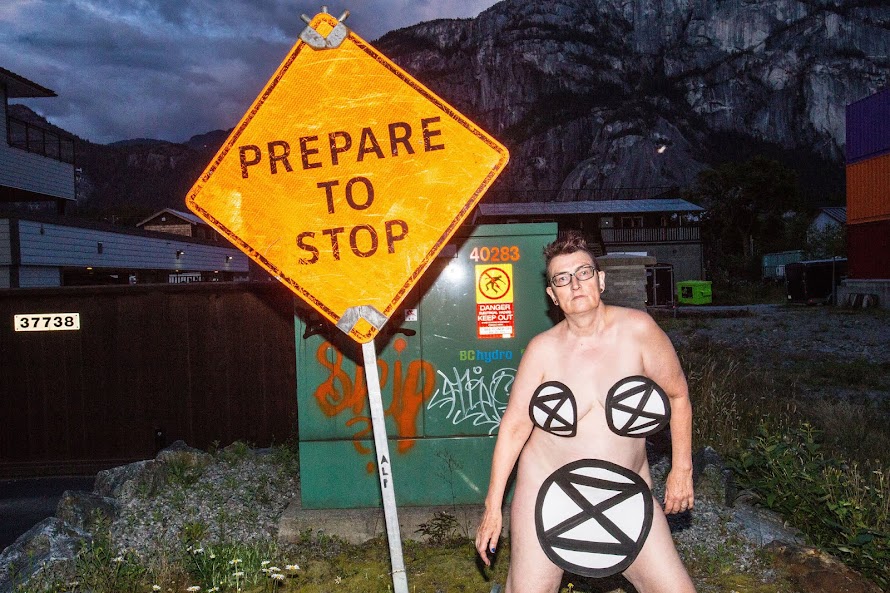

As an academic and as an artist, my work in the Human Body Project is about where my healing intersects with world healing: vulnerable body=vulnerable planet. My work is challenging, difficult to categorize, and experiential. There is no space for commercialization or self-advancement. Like Pakki Chipps, I'd share for gas money.

Tse Tsa Watle, as an entity in the university, is challenging and difficult to categorize. For me, it is experiential in the sense that the intention of sincerely holding the space for "tse tsa watle," the concept, allows for an experience that moves beyond the disciplines.

Dilemma: how much difference can the Human Body Project or Tse Tsa Watle or Dr. Chipps's teachings make? We share the same problems of lack of funding, low audience, and almost no place within the ownership structures, legal entities, categories, disciplines, departments, etc.

My own feelings about this situation are not positive and rageful. And I haven't even addressed my own dilemma of understanding myself to be a woman with indigenous wisdom, who happens to be white. Still, I am grateful that Tse Tsa Watle exists and I am grateful to Dr. Virginia McKendry, Greg Sam, and Bill White who are the actual people holding the space (there may be others that I don't know about). I'm grateful to Dr. Chipps for sharing herself and her knowledge so heartfully.

Dr. Chipps's website is chamasart.com.

Watch a brief video presentation describing various aspects of the Tse Tsa Watle project: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATTSOfJB4YM

All past full-length Tse Tsa Watle presentation videos may be found here: http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL5D128D35C65E8DE4&feature=plcp and http://www.youtube.com/user/RoyalRoadsUni

View an award-wining video essay created by an RRU BA in Professional Communication student team in regard to the TTW project: http://vimeo.com/44170189

Read a story RRU's Community Relations people did to celebrate and acknowledge the students' work and the TTW initiative: http://www.royalroads.ca/news/coming-together-interdependence